JFK PROJECT

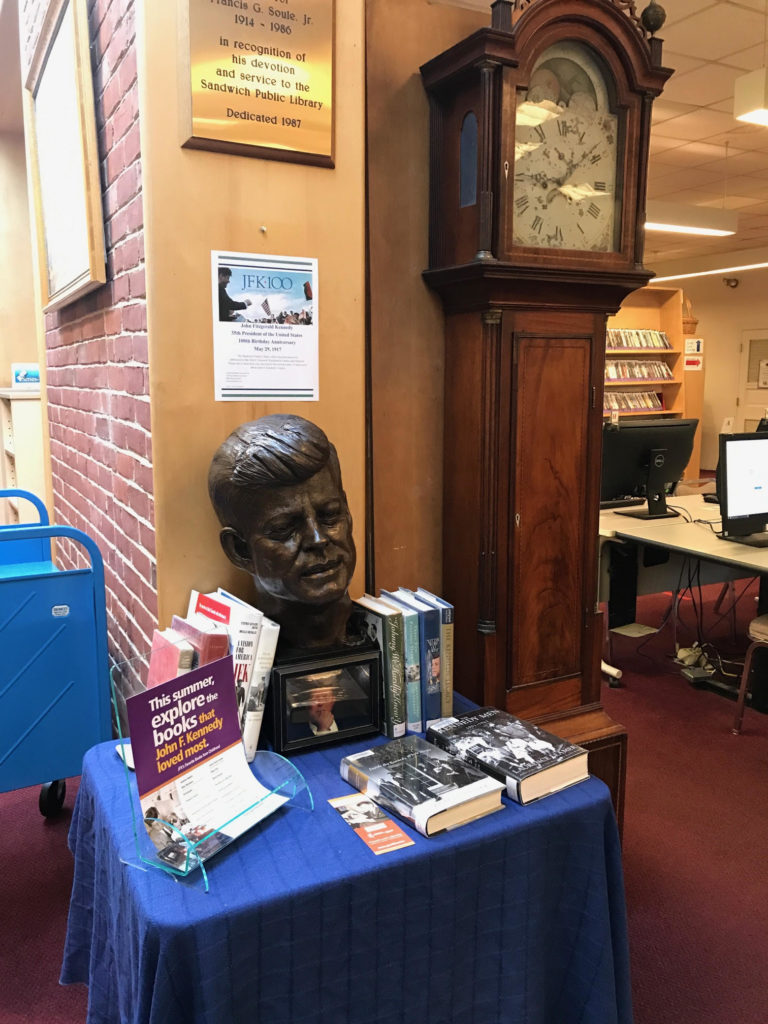

The bronze bust of John F. Kennedy, created by world renowned sculptor, Lado Goudjabidze, is being exhibited in public locations during the 100th anniversary of his birth. The JFK Project encourages people, young and old, to write down their thoughts on the 35th president of the United States. (Below are photos of the JFK bust at the Yacht Club in Duxbury, MA. and Sandwich Public Libary)

“War will exist until that distant day when the conscientious objector enjoys the same reputation and prestige that the warrior does today.” JFK

“War will exist until that distant day when the conscientious objector enjoys the same reputation and prestige that the warrior does today.” JFK

Armistice Day which marked the day fighting stopped on November 11, 1918 had to be cancelled when in October 1939 British troops landed on mainland Europe almost exactly 25 years after the last time. The public meaning of the Armistice after what came to be called World War One – victory and warning against future wars – was dependent on there being peace. With the declaration of another war this meaning was shattered but was subsequently reconstructed, the ‘war to end war’ forgotten, and the ‘nobility’ and ‘necessity’ of war burnished. In a new guise and periodically refreshed to meet new PR challenges, Remembrance Sunday came to serve as a justification of war and exhortation to eternal vigilance – the passing of the torch – and selling red poppies now the valuable corporate logo of the British Legion. Today for some Remembrance Day has private significance; for the rest of us its public face is a spectacle appropriated for specific financial and political purposes.

In this centenary anniversary of World War One we are urged to think deeply about that war. We would do well to note that by the time Armistice Day was cancelled in 1939 it had already changed profoundly from its original public conception as a time for mourning and reflection on loss of life to a self-validating day out for the military, a powerful recruitment tool for the War Office and lots of ‘victory’ parties.

In 1914 people may have thought they were fighting German militarism but not a year has gone by since when the British military have not been engaged in fighting somewhere in the world. No other country can boast of or be shamed by such a record. Militarism is alive and well in today’s Britain.

Militarism is not just about the outward show of bellicose rhetoric, medals and soldiers proudly marching through towns when returning from wars, or parading in front of the monarch in serried ranks. It is the cast of mind and belief system that favoured the age-old values embodied in war fighting. A cast of mind that sends princes and prime ministers to sell weapons to even the most unsavoury despots, a cast of mind that funds research and production of ever more devastating weapons and associated technology. A cast of mind that believes that men and women trained to kill can provide an especially beneficial role model in schools and pass on their military values to young people. A cast of mind that without apparently us noticing is eyeing our cities as battlegrounds to be surveilled and patrolled where we are viewed with suspicion and have to prove our ‘innocence’. As technology originally funded by and designed for the military is leaching into the civil sphere so is its originating mindset. The distinction between policing, intelligence and the military becomes blurred as does the distinction between war and peace and local and global operation.

War has become the dominant metaphor to describe much of the world around us – war against drugs and crime, war against terror, against insecurity. These are not just a sloppy use of language but reflections of stealthy militarisation of a wide range of policy debates as well as popular culture.

War – the struggle for control – for people in Britain has mostly been a distant event. Today that struggle for control is in our streets.

The deeper inspiration for the white poppy lies in the widespread movement against war and militarism in the early years of the 20th century. It urges us to challenge militarism and work for a culture of peace. It urges us to have the courage of the conscientious objector of WW1 to resist the temptation to participate in the war machine.